Growing up in Montana, a common explanation for the sometimes idiosyncratic nature of politics is that “Montana is a libertarian state.” Right off the bat, I am always skeptical of people and places with a supposed ‘libertarian streak.’ In my experience, these people support ‘small government’ whenever regulations threaten to affect them personally, and large government when it preserves their interests. This dynamic was captured perfectly by Montana State Legislature last week. The Flathead Beacon reports:

A bill that would have prohibited most city and county zoning regulations and other restrictions on accessory dwelling units (ADUs), also known as mother-in-law units, failed in the state legislature.

The bill… would have prevented local governments from adopting zoning regulations that prohibit ADUs on single-family parcels or enacting other restrictions such as parking limits, square-footage limits and additional building standards.

“The demand for smaller housing exists,” Hertz (R-Polson) said at the March 29 hearing. “The disconnect between housing supply is due in part to cities’ indirect discouragement of diverse and flexible housing options.”

Bill Revising Laws for Accessory Dwelling Units Dies in Senate

ADUs provide a simple method to organically increase housing stock, especially for those looking for small, affordable rentals. And while allowing ADU’s would be wildly insufficient to solve Montana’s complex housing crisis, opposition to a simple and ostensibly bipartisan measure like this is extremely disconcerting. This bill failed in a bipartisan fashion, with 15 Republicans and 13 Democrats voting against the measure. Opposition to a common-sense measure such as this is a bad portent for the state’s response to housing trends already in motion. We can look to places more populous to see the dramatic consequences of Montana’s current policies.

Montana Needs Housing

If you have lived in Montana, you’ve doubtless heard gripes about the ‘Californians’ moving in, jacking up home prices, and generally making life worse for the ‘real Montanans.’1 A pretty hypocritical position for those who aren’t Native Americans. Much of this sentiment is rooted in just griping, but to the extent that it reflects reality, it manifests itself in housing.

Places like Bozeman and the Flathead Valley are increasingly popular, especially during the pandemic when many white-collar jobs shifted to remote work. Driven out by housing shortages on the coasts, these workers have flocked to Montana (it’s a great place to live!). This shock to the housing market resulted in skyrocketing housing demand, sending shocks across the market. These trends are particularly devastating for those already economically stressed.

The U.S. Census Bureau found that the median household income for a household in Gallatin County is around $61,500 per year in 2018 dollars. In Bozeman specifically, the median household income is just under $52,000. For those making less than that median, staying here while housing prices are increasing quickly and consistently is getting harder and harder, said city commissioner Terry Cunningham. “We are approaching a crisis point in Bozeman,” said Cunningham, who is the commission liaison to the City Affordable Housing Advisory Board.

‘Crisis point’: How the Gallatin Valley’s hot housing market leaves people behind

Housing costs are highly regressive, with most working-class households spending over half of their income on housing. A similar distribution applies to renters, who are much more likely to be low-income than homeowners. When housing prices rise, homeowners can capitalize on their real estate investment by selling, 2Buy our families’ house, by the way! while tenants merely see their rents rise even further. This power imbalance between buyers and renters often reinforces itself, with NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) homeowners organizing to limit new housing developments and capitalize on the supply shortage. This vicious cycle both exacerbates homelessness and widens income inequality. Beyond this, housing policies like redlining and single-family suburbs have a deep history of racism, including policies that discriminated against Native Americans.

The government’s response to shortages in housing can either alleviate or deepen these inequalities. Restricting the market’s ability to respond with solutions like ADU’s is the precisely wrong direction for the state. Real Estate is decreasingly elastic, and the lead times involved in creating new housing supply are significant, meaning that supply shocks such as those taking place across cities in Montana aren’t quickly corrected by the market. Solutions like ADU’s are perfect because their simplicity in both construction and regulation means they can increase housing stock quickly, helping with the growing inelasticity of housing supply. More broadly, failing to reform status-quo zoning policies is disastrous for the housing market, climate change, and economic opportunity.

Mandating Market Failures

“There’s nothing in (the bill) that requires any of these new units to be affordable … It allows for unfettered building for things like guest houses and tiny homes on single-family lots,” said SK Rossi, a lobbyist representing the city of Bozeman.

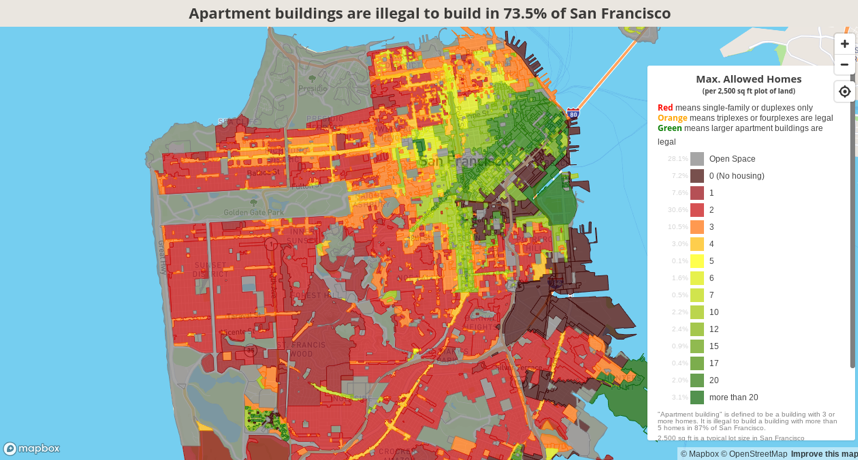

On a first pass, Rossi’s sentiment seems logical: an affordable housing crisis demands affordable housing. First off, the Montana legislature is opposing affordable housing initiatives as well! More importantly, when you don’t allow the construction of enough housing, all housing becomes luxury housing. Instead, building market-rate housing reduces prices across the market. San Fransisco has shacks selling for $2 million and debilitating homelessness not because high-rise apartments are unaffordable, but because apartment buildings are illegal to build in 73% of the city. The problem with San Fransisco’s urban design is not the penthouse downtown, but the acres of single-family homes extending across the rest of the city.

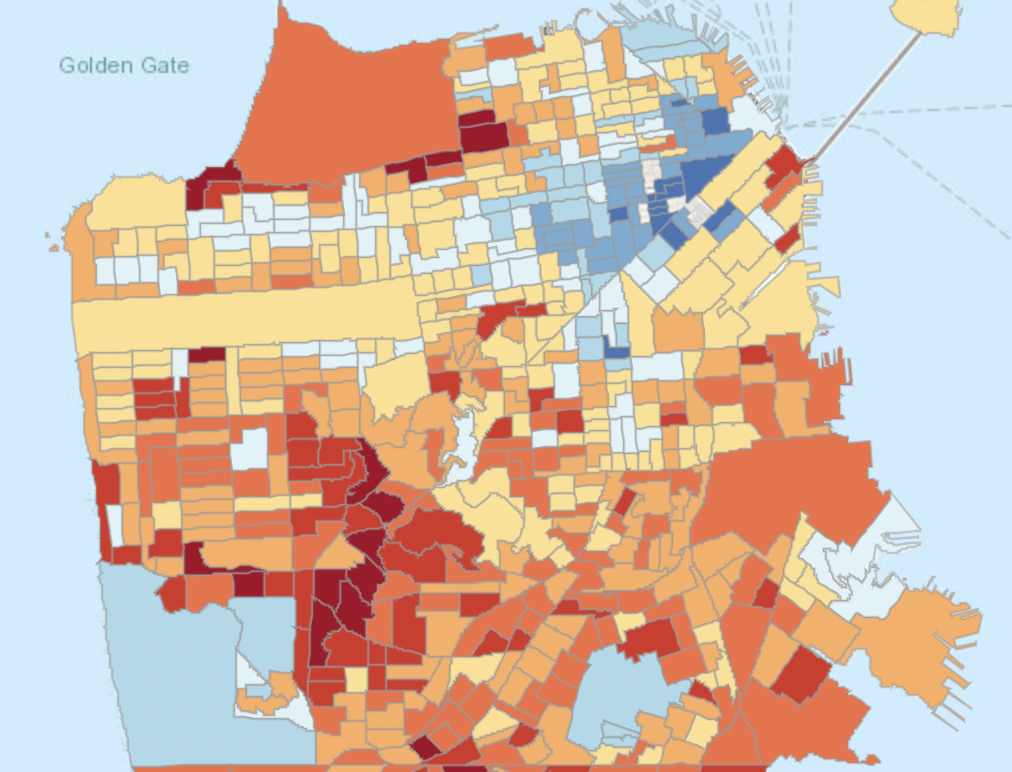

Can you spot a correlation between these two photos?

There is nothing wrong with mandating portions of housing projects to be affordable; it is unlikely that the free market would ever provide sufficient housing stock for the lowest income populations. In fact, there are a lot of interesting and inventive ways to ensure that a growing real-estate market is distributed equitably. However, these policies must be coupled with a willingness to allow development where the market demands. Instead, the admirable goal of directly creating affordable housing is often used as a cudgel by NIMBYs nationwide to deride all new housing projects as a gift to the rich instead of a natural response to increased demand. No matter how progressive the concerns behind opposing upzoning are, the result is a small-c conservative preservation of an unsustainable status quo, as well as wildly regressive outcomes.

Taking another look at Rossi’s statement with this in mind, it reads more like this:

Bozeman: doesn’t allow market rate housing

Also Bozeman: why are homes so expensive?? I blame Californians.

Densityphobia and Climate Change

Several people spoke in opposition of the bill, arguing it would attract more short-term rentals to cities, strain infrastructure and add density.

When an economy is increasingly based on tourism, short-term rentals will increase regardless of whether you build ADUs. Regardless, giving homeowners the ability to rent out a mother-in-law unit is not going to radically alter the density or character of any city in Montana. City planners quoted in this article disagree:

“Where there’s something in Kalispell or Whitefish or Bozeman, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to have the same rule applied to Glendive or Miles City,” [Kalispell Senior Planner PJ] Sorenson said in an interview. “Land use by nature is a local type of thing, so you have to take in local conditions of what the local community wants, and it’s hard to do that on a state level… having that one size fits all [regulation] doesn’t work.”

Opponents to these upzoning measures always sound like they think the government is mandating additional construction, not just allowing it. If no homeowners in Glendale or Miles City see a massive financial benefit in building and renting out an extra unit on their property, then they just won’t build it and nothing will change! The local conditions dictate the market’s response.

But let’s imagine that the bill up for consideration was not a minor change to the housing code but instead a large-scale reimagining of the policies that govern urban design in the state; a bill that would appreciably increase density. Montana’s population is growing, and the trends of remote work and urbanization are not going to reverse. Furthermore, the pernicious effects of climate change that are already being felt in coastal regions will doubtless drive more internal migration to places like Montana. With these factors in mind, increasing the density in the center of Montana’s cities is a policy outcome that the state government should be encouraging. When housing demand increases, the alternative to density is not everything staying the same, but sprawl. And suburban sprawl, enabled by restrictive zoning policies, is really, really bad.

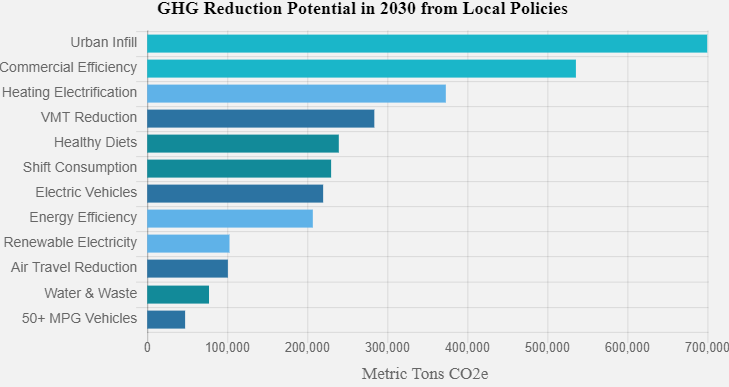

The suburbs are designed for cars, so it is no surprise that suburban sprawl is responsible for an outsized portion of carbon emissions, as Sam Deutsch points out:

Switching from a personal car to mass transit is one of the best things people can do to reduce their carbon emissions. Building more housing makes that easier, and it’s a large part of the reason that so many YIMBY policies are also climate policies.

It’s hard to overstate the level of importance of these policies for a zero-carbon future. Urban infill is the #1 policy that localities can undertake to reduce their carbon footprint. 3Facts like this are also why I get upset at fake climate groups like Sunrise that actively support harmful climate policies.

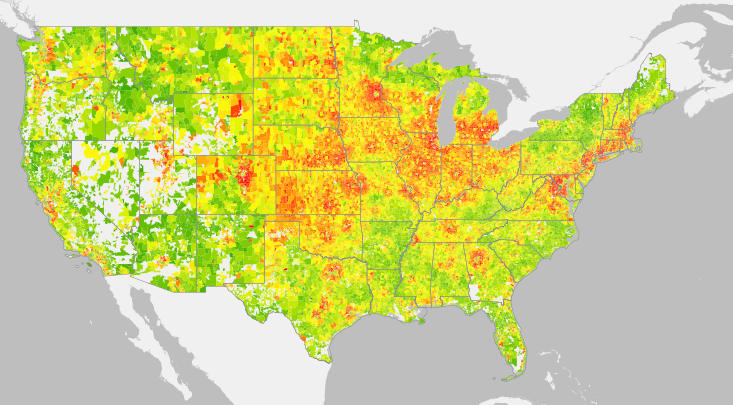

This characteristic is most starkly seen when plotting household carbon emissions by zip code:

Metropolitan areas look like carbon footprint hurricanes, with dark green, low-carbon urban cores surrounded by red, high-carbon suburbs. Unfortunately, while the most populous metropolitan areas tend to have the lowest carbon footprint centers, they also tend to have the most extensive high-carbon footprint suburbs.

Berkeley News

You can see this effect surrounding basically every city in the country. Remember that the urban cores of American cities are very bad at encouraging carbon-efficient mass-transit policies compared to their European counterparts, but even those unoptimized cities are green utopias when compared to the haloes of carbon that surround them. Lo and behold, a carbon footprint map of the Bay Area closely mirrors the zoning map shown earlier.

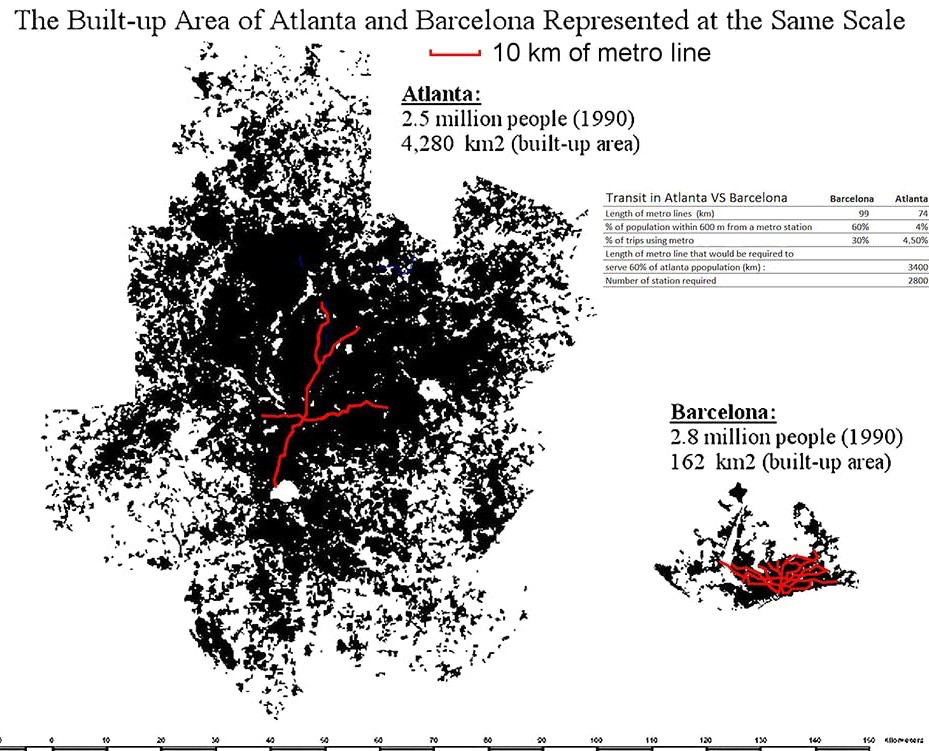

Looking past the climate catastrophe of sprawl, Montana is desirable in the first place because of accessible and widespread public lands and wilderness areas. Sprawl is directly antithetical to the idea of a wide-open, untouched environment because it is so terrible at sustaining a population. Enabling even moderately dense urban cores in highly sought-after places in Montana is entirely compatible with preserving the spaces that make Montana the best state in the US. 4I am being completely objective. As an avid climber, skier, and hiker, I would much rather have a city in Montana that follows the development pattern of Barcelona than Atlanta.

Once you recognize the benefits of density, there’s actually a lot of cool stuff you can do to encourage livable, community-building, green, inclusive communities. Policies that encourage walkable city centers, protect biking, build up electric vehicle infrastructure, and encourage upzoning are not especially challenging or administratively prohibitive. Creating a robust transit system with density near transit stops is similarly beneficial.

The side effect to all of these investments in infrastructure is that you need people to build it, and then more housing for those workers, and then the cycle repeats. That cycle could also be called economic growth! Taken to an extreme, a recent study found that upzoning in restrictive municipalities like New York, San Jose, and San Fransisco would increase GDP by an estimated 17-36 percent!

To step back from this perspective, Kalispell, Montana is of course far different than San Jose, California. Allowing ADU’s would not transform it into such. But the principles of housing supply and demand hold in every market, and the housing shortage we are seeing is a microcosm of those seen in many larger cities across the country.

Montana, Don’t Throw Away Your Shot

The deep housing shortage that many municipalities in Montana face (and will face more in the future!) is unenviable for many of its most vulnerable citizens. However, there are many, many places across the country and the world that would kill for the economic growth and excess housing demand that so many Montanans deride. As Matthew Yglesias points out in the excellent One Billion Americans, many cities in the Rust Belt are coping with the reverse problem, with an endemically depressed market putting the cities into a death spiral (emphasis added).

We have several major cities—and dozens of smaller ones—slowly wasting away due to population decline.

Shrinking cities offer a worse balance of taxes to services than growing onesbecause today’s smaller population needs to pay pension obligations incurred by yesterday’s larger ones. They don’t attract investment because they are shrinking and don’t need many new buildings. The lack of new investment creates a lack of job opportunities, which encourages further shrinkage.

The main virtue of the depopulating city is that houses there are cheaper than in more desirable places. But that sets in motion a negative selection—the only people sticking around are those without the means to leave, a population that also lacks the means to pay taxes and support local businesses.

Soon enough, the cheapness of the houses itself becomes a liability… In many of these declining cities the purchase price of a building is lower than the replacement cost of rebuilding that same structure in place. “That’s why these cities are cursed with derelict structures and abandoned buildings that become eyesores and havens for literal vermin.

But the impact on non-vacant structures, though harder to see, is insidious as well. A landlord whose property is worth less at sale than its replacement value has no incentive to do proper upkeep on his buildings. Tenants will get, at best, what they are legally entitled to and realistically less than that because enforcement is spotty. That means inadequate heat in the winter, grim conditions all year round, and often legitimately dangerous problems of mold and rodents.

The undesireable situation described here is all too common in significant swaths of the country. Many places in Montana are blessed with fast economic growth and general desirability, with growing tourism and health care sectors. Montana is the 48th most dense state in the US, but is not exempt from worldwide trends of urbanization. We are therefore well-placed to learn from the widespread failure of postwar suburbanization and forge a more equitable and prosperous future for our cities. State regulations could harness and guide the market to further the creation of density and climate-friendly policies as it grows. Instead, blessed with opportunity, we resort to hand-wringing, insularity, and kvetching about the prospect of economic prosperity. Embracing and encouraging change is the best way for Montana to proceed.

- 1A pretty hypocritical position for those who aren’t Native Americans.

- 2Buy our families’ house, by the way!

- 3Facts like this are also why I get upset at fake climate groups like Sunrise that actively support harmful climate policies.

- 4I am being completely objective.